Update: here's a picture of how the original spindle looks like.

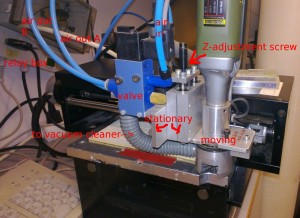

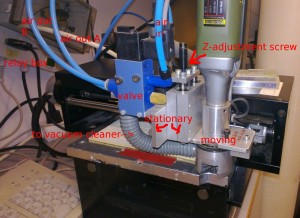

By popular demand, some pictures of the modified LPKF Protomat S91 PCB-mill (featured here). The spindle assembly on this mill has been re-built. The original has an LPKF spindle motor and a solenoid for pushing/pulling the spindle up/down along the Z-axis. This modification uses a Proxxon spindle and an air-cylinder for the Z-movement.

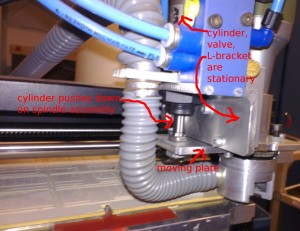

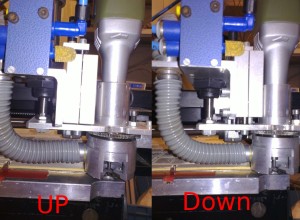

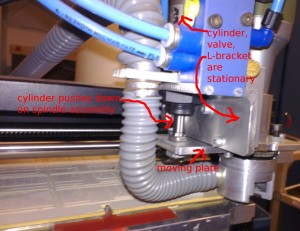

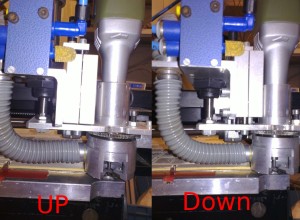

These two pictures shows the spindle from the front. Pressurized air is input to the valve which routes it either to output A or B. This pushes the air cylinder either to the UP or DOWN position. The cylinder pushes on an aluminium plate to which the spindle motor is attached. The moving plate is guided by a linear bearing. A screw at the top of the linear bearing allows adjustment of the Z-depth of the DOWN position. A spring at the top also helps with pushing up the spindle.

This picture shows the cutter. A vacuum cleaner attaches to they grey tube, and sucks away all chips produced during drilling and milling. A cylindrical cover or "door" around the spindle (now open for tool change) is rotated shut when the machine runs.

This shows the electrical connections. The modification of the spindle involves connecting a cable from the second connector from the right to a custom-built relay box. Otherwise the connections are as on a standard machine.

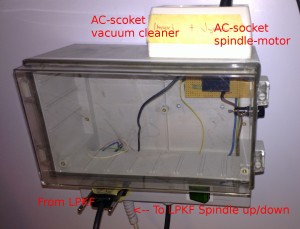

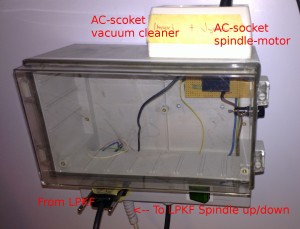

This shows the relay box. The cable from the base of the machine is used to control three On/Off devices: vacuum-cleaner on/off, spindle-motor on/off, and Z-axis up/down. The spindle-motor and vacuum cleaner connect to standard AC-mains sockets. The Z-axis up/down control signal is connected to the air-valve on the spindle assembly.

Some additional views. Note how small the required Z-movement is.

These pictures show the air-cylinder.